Trading One Disaster For Another – We Can Do Better, and We Will

By Miriam Gordon, guest blogger

Berkeley City Council hearing on Disposable Free Dining ordinance. All photos courtesy of UPSTREAM.

I haven’t heard a single airplane fly over my San Francisco home since March. With the nearly complete cessation of traffic of any kind, birds were the primary noisemaker outside my urban windows. It was beautiful. I was thinking that the silver lining to the COVID-19 pandemic would be reduced carbon emissions.

Instead, the pandemic has provided a way to gauge how much has to change to save ourselves from the worst climate change scenarios. A study recently released in Nature Climate Change estimated that in April daily CO2 emissions decreased globally by 17%, while the annual decrease will be much lower (-4.2% to -7.5%). It concludes that we would have to continue annual reductions on this order for the next few decades to limit warming to an increase of 1.5°C, the target set under the Paris Climate Treaty.

How will it be possible to achieve such reductions? Bringing industrial operations and auto and airplane use down to the levels achieved in April, at the height of world-wide response to the pandemic to date, will require nothing short of a sea change.

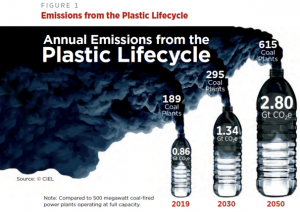

Infographic from Center for International Environmental Law

But what about the plastic? As cars become more efficient and renewable energy increases, the fossil fuel industry is looking to divert its glut of fracked gas into plastics. The chemical industry is investing $164 billion on 264 facilities in the U.S., mostly to turn fracked gas into plastic. By increasing plastics used for single use food and beverage packaging in developing countries and for products sold to millennials in the U.S. and Europe, the industry expects plastics use to quadruple by 2050. The associated greenhouse gas emissions will reach 1.34 gigatons by 2030 — equivalent to the emissions from 295 new coal-fired power plants.

But some of the biggest problems with plastic may prove to be the undoing of its growth. First there is the challenge of managing waste. China’s ban on imports of dirty plastic and paper packaging unveiled the myth that plastic and food packaging can be recycled. No longer able to export products proven to be unrecyclable, communities throughout the U.S. are sending them to landfill and incineration. And it’s very nature as a material that is both disposable and lacking any real value has resulted in a global litter problem (the equivalent of one garbage truck of plastic enters the ocean every minute) that has resulted in many people viewing plastic as public enemy #1.

COVID-19 created an unprecedented opportunity for the plastics industry. Playing on our collective fears, the industry jumped into action. Early on they suggested to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that reusable bags spread coronavirus, using junk science to try to block plastic bag bans across the U.S.

Miriam Gordon at Muuse reusable cup launch in San Francisco

None of this jibes with the current science on COVID-19. A statement signed by 125 public health professionals points out that choosing single-use instead of reusable materials doesn’t provide more protection, since the virus isn’t known to be transmitted by touching surfaces. According to the CDC, FDA, and USDA the virus is not transmitted by surface contact. Nonetheless, with the plastics industry influencing decision-makers — and with well-meaning health officials using an abundance of caution — single-use plastics are a primary tool in the response to COVID-19.

This pandemic arrived just as UPSTREAM and others in our national reuse movement were on the precipice of changing the throw away culture in food service. I helped draft Berkeley’s first-of-its-kind policy that in 2019 banned disposable foodware in restaurants and imposed a charge for disposable take-out cups, making reusables the cheaper option. Similar policies followed in seven California communities and the City of Vancouver, B.C. Others were about to be enacted in cities across the U.S. in 2020.

Unfortunately, due to COVID-19 several states suspended their plastic bag bans and said ‘no’ to customers’ reusable cups and bags, buying straight into the plastics industry playbook. Switching gears to defend reusables and debunk the myth that disposable plastics are safer has slowed our progress on policies that end the throw away culture. Fortunately our efforts have made an impact, as recently California Governor Newsom declined to extend his executive order that put the state-wide plastic bag ban on hold. San Francisco, Alameda, and Santa Clara Counties, plus the City of Berkeley, have since lifted the ban on reusable shopping bags.

Vesselwork’s lending library of reusable cups

In the end, I know we will win because switching to reusables saves money, and business opportunity in this sector is growing. People are angry that their communities are being inundated with plastic litter and waste — and they demand change. With public support behind ending the throw away culture and the economics on our side, it’s not a question of whether we will win this battle, it’s a question of when… and whether it will be in time to help hold the line at 1.5C°

— Miriam Gordon is the Policy Director for UPSTREAM. She has long had a devotion to tackling waste and toxics issues to make the world a better place. She joined UPSTREAM in 2016 to focus solely on ending the throw away culture, which she views as driving every aspect of environmental devastation.